How do you write about the man who made your dream come true? He made me into a pilot and I will be forever grateful. He was my teacher, my mentor, and my flying buddy through the years, and he was always a true friend. His life speaks for itself better than I could ever do. -- EY

Woody always knew what he wanted to do.

He got his first airplane ride at the ripe old age of 5, in a Fokker C-2 at Hendersonville, NC, October 1, 1923.

And so a fate was sealed.

A few years later, he and his

buddies were figuring out how to build airplanes. They were

doing it the hard way, by hanging out at the airport, looking at every

airplane that came

along, cadging rides when they could and washing, parking, fueling, fixing, and propping them

when they couldn’t.

A few years later, he and his

buddies were figuring out how to build airplanes. They were

doing it the hard way, by hanging out at the airport, looking at every

airplane that came

along, cadging rides when they could and washing, parking, fueling, fixing, and propping them

when they couldn’t.

An early

project, mercifully unfinished, was the Moronca (top),

named in unplagiaristic honor of the considerably more popular Aeronca.

They built a glider

(bottom) and took turns towing it down the runway with a stripped down Model T.

An early

project, mercifully unfinished, was the Moronca (top),

named in unplagiaristic honor of the considerably more popular Aeronca.

They built a glider

(bottom) and took turns towing it down the runway with a stripped down Model T.  Real lessons were expensive and hard to

come by. Oscar Meyer, whose father owned the

airport, taught himself to fly, then started teaching his younger friends. Back in the

hills, licenses were not altogether commonplace, but nobody much cared. You could fly or

you couldn’t. Woody soloed July 3, 1936 in a

J-2 Cub.

Real lessons were expensive and hard to

come by. Oscar Meyer, whose father owned the

airport, taught himself to fly, then started teaching his younger friends. Back in the

hills, licenses were not altogether commonplace, but nobody much cared. You could fly or

you couldn’t. Woody soloed July 3, 1936 in a

J-2 Cub.

At commencement, Woody and his classmates were told that, as Citadel graduates, they could command a high salary. Alas, this was 1939. The country was preparing for war and still recovering from the Great Depression. Woody commanded his high salary for a time on a mud scow in the Potomac River, watching the airplanes overhead and dreaming. He finished his pilot certificate with the Civilian Pilot Training Program and started trying in earnest to get into the Air Corps.

No doing.

He was married. He was underweight. His paperwork was so far down the pile that it would never see daylight. He finally went on active duty as a 2d Lieutenant observer with the District of Columbia National Guard. He flew submarine patrol from Langley Field in a single engine Curtiss O-52, thus beginning his lifelong aversion to flying over water.

Then it was off to Army Air Corps flight training. He earned his wings and was assigned to the Navigation School at Hondo, Texas. While there, he flew everything he could get his hands on and accumulated 2300 hours in less than two years. He was selected for B-29s and sent to Florida for initial training and then to Kansas for B-29 transition. At Salina, the new B-29s growing pains were evident. Flaps caught fire, engines overheated, brakes gave out, engines swallowed valves at every opportunity. After three precautionary landings in a single week, the other aircraft commanders teased Woody: "Faison, can't you land without declaring an emergency?"

At last, crews were assembled and assigned to Saipan for combat. Woody flew 35 missions as aircraft commander and flight leader, all over 1500 miles of open ocean. The water bothered him more than the flak did. He and his crew were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism and extraordinary achievement.

After the war, Woody continued his Air Force career

(after all, that's where the airplanes

were!). He flew the Berlin Airlift, tankers, ran field maintenance

and periodic maintenance

squadrons, and commanded the Best In SAC 567th Missile Squadron at

Fairchild AFB.

After the war, Woody continued his Air Force career

(after all, that's where the airplanes

were!). He flew the Berlin Airlift, tankers, ran field maintenance

and periodic maintenance

squadrons, and commanded the Best In SAC 567th Missile Squadron at

Fairchild AFB.

When he wasn't flying on the taxpayers' dollar, he was flying his own airplane, first an Aeronca, then a Bellanca. Cranking the gear up on the Bellanca on a day like this took some muscle!

Eventually, retirement loomed. Woody sold

the Bellanca, bought a Cessna 150, and moved back

to South Carolina to start Palmetto Air Service. He started pestering the owners of

the

Isle of Palms airport to let him run it. He wrote letters, he made phone calls, he wrote more

letters. Eventually, they told him

that if he really wanted to, he could give it a shot, but he'd

owe them two cents for every gallon of gas he sold. With that, Woody was

off. He hauled in

a portable building that became Palmetto Air Service's international headquarters. He bought an

above-ground gas tank

and a pump. He made tiedowns for airplanes and a set of homebrew

runway lights for night landings.

Eventually, retirement loomed. Woody sold

the Bellanca, bought a Cessna 150, and moved back

to South Carolina to start Palmetto Air Service. He started pestering the owners of

the

Isle of Palms airport to let him run it. He wrote letters, he made phone calls, he wrote more

letters. Eventually, they told him

that if he really wanted to, he could give it a shot, but he'd

owe them two cents for every gallon of gas he sold. With that, Woody was

off. He hauled in

a portable building that became Palmetto Air Service's international headquarters. He bought an

above-ground gas tank

and a pump. He made tiedowns for airplanes and a set of homebrew

runway lights for night landings.  From the rundown and untended grass strip by

the Inland Waterway,

he built a thriving airport community. There were Aeroncas and Bellancas and Cubs. There

were Cessnas and Pipers

and Beechcrafts. A B-25 landed there on its way to the museum on

the Yorktown. (It was barged the rest of the way.) Friendships began

that flourished for decades.

From the rundown and untended grass strip by

the Inland Waterway,

he built a thriving airport community. There were Aeroncas and Bellancas and Cubs. There

were Cessnas and Pipers

and Beechcrafts. A B-25 landed there on its way to the museum on

the Yorktown. (It was barged the rest of the way.) Friendships began

that flourished for decades.

The grass strip on the waterway finally closed to make way for development. Plans were already in place for a replacement airport, but it wasn't ready yet. Undeterred, Woody moved lock, stock, and portable HQ to a corner of Charleston International Airport for the duration. It wasn't an ideal setup -- Cessna 152s and heavy Air Force airplanes are not a comfortable mix -- but it worked.

At last, the new East Cooper Airport

was

almost ready. It didn't have an operator yet, but needed to open, so Woody agreed to move early and provide a

presence on the field.

The portable headquarters from the Isle of Palms had yet another home, since the terminal wasn't

complete. A few days after he arrived,

a skin-and-bones black lab walked out of the woods, instinctively knowing a

sucker when she saw one. Woody and Rudder became inseparable

companions for the next 16 years.

At last, the new East Cooper Airport

was

almost ready. It didn't have an operator yet, but needed to open, so Woody agreed to move early and provide a

presence on the field.

The portable headquarters from the Isle of Palms had yet another home, since the terminal wasn't

complete. A few days after he arrived,

a skin-and-bones black lab walked out of the woods, instinctively knowing a

sucker when she saw one. Woody and Rudder became inseparable

companions for the next 16 years.

Hurricane Hugo in 1989 took a toll on everyone in the area. The airport lost its T-hangar, but the terminal building survived. All Palmetto Air Service's airplanes except the Cub and the original 10F rode out the storm in Orangeburg. The Cub was in pieces in the T-hangar, but the hangar collapse kept her from blowing away.

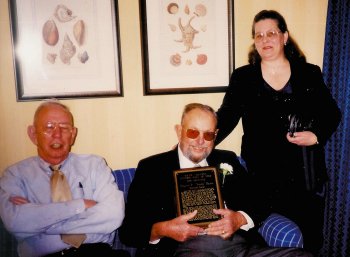

Woody's civilian awards and recognitions were many. In 1999, the South Carolina Aviation Association inducted him into the South Carolina Aviation Hall of Fame. He's shown here relaxing after the award ceremony with his brother Walter, a long-time employee of the FAA, and Edna, who surprised him by making the presentation speech.

Two years later, the Charleston County Aviation Authority (owners of the East Cooper Airport) named the access road to the airport in honor of Woody. They even gave him his own street sign so he didn't have to swipe the official one.

The Federal Aviation Authority honored Woody with South Carolina's first Wright Brothers Master Pilot award, presented to him in 2005 by Carolyn Blum, FAA's regional director. The award recognized his "dedicated service, technical expertise, professionalism, and many outstanding contributions that further the cause of aviation safety" during more than 50 years of accident-free service to aviation.

In 2007, the Charleston County Aviation Authority voted unanimously to name the airport where Woody flew for so long after him. The airport is now officially Faison Field - Mt. Pleasant Regional Airport.

Through it all, Woody loved to fly and he loved to teach. Many of his own students are now teachers, too. Some graduates went on to fly for careers and many others have flown for personal reasons just as successfully.

Airports need dogs, and we'd all felt the loss of Rudder. This new dog appeared at the right time. We were just going to go look at the dog, not bring her home, but she put her head in Woody's lap and used those big brown eyes to get just what she wanted. It was a foregone conclusion anyway, since Woody had spent the entire drive to the shelter picking out her new name.

Woody flew and taught until just a few days before

he passed away. Arthritis had taken its

toll of his once-tall stance, and walking had become increasingly difficult. Once he

folded

himself into an airplane, though, he was as limber and as skilled as ever. Many came to honor him

at his funeral and at a Tribute Day

held at the airport near what would have been his 90th birthday.

An Air Force C-17 made a low pass over the field in his honor, and his

colleagues performed

an aerial salute.

Woody flew and taught until just a few days before

he passed away. Arthritis had taken its

toll of his once-tall stance, and walking had become increasingly difficult. Once he

folded

himself into an airplane, though, he was as limber and as skilled as ever. Many came to honor him

at his funeral and at a Tribute Day

held at the airport near what would have been his 90th birthday.

An Air Force C-17 made a low pass over the field in his honor, and his

colleagues performed

an aerial salute.

May we all be as lucky as he: to do the things he loved throughout his life, to honor and be honored, and to be always surrounded by good friends and companions.